about Christina de Vos

part one of two

deze pagina in het Nederlands

For a long time, Christina de Vos was very reluctant to call herself an artist. She grew up in rural Holland, in every way far removed from metropolitan culture, and was nearly oblivious to modern, let alone contemporary art, right up to the start of her professional training. In a way, this naivety has stayed with her, and in fact she feels more akin to reclusive and outsider artists, than at home in the bustle of the art world.

|

|

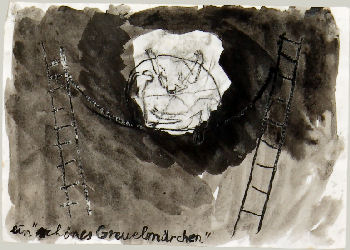

above: figure with ladder, 1985

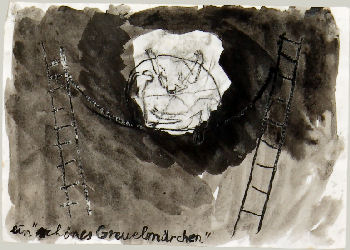

right: ladders and wheels, 1984/85

|

She attended art school in Rotterdam, intent on becoming a traditional painter, but she soon veered off towards the draughtsmanship that, to this day, pervades her work. Christina concluded her study in 1987, with a massive series of small drawings on scrappy pieces of paper, and a tetraptych (or rather four matching large drawings on canvas). It did earn her accolades, a prestigious gallery show, and the inevitable label 'promising', that blandest of epithets.

Her precarious academic flowering presented itself as 'ein schönes Greuelmärchen' (a beautiful horror story): theatrical depictions of cruelty, stagings reminiscent of freakish sideshows, martyrdom, and worse. The numerous headless bodies and featureless heads certainly added to the gloom of these works, but they also attested to both Christina's fear of accidental self-portraiture, and her reluctance to show human shapes she felt she hadn't mastered yet.

|

|

|

|

The considerable hardship that went into producing works of such brooding intensity, was more than she could shoulder. Cut loose from the safe moorings of academia, Christina had to reinvent her craft, to find a humanly feasible way to reattain the quality of those early works. She began drawing from paintings and sculptures she admired, most notably Matthias Grünewald's sorrow-laden, pain-drenched Isenheim Altarpiece. So she did continue to depict man's inhumanity to man, but made it bearable by seeing it through the eyes of a fellow artist.

landscape (entombment), after Grünewald, 1988

|

Christina's works after old masters are not mere sketches, but accomplished, mature drawings that capture the essence of the art from which they are derived. And they are more than studies towards an oeuvre that can stand on its own merits, for copying lies at the very heart of Christina's artistic process: the admiration she feels for many old and some more recent masters, is really a form of cupidity, a wish to literally own their work.

Drawing is Christina's way of learning how her idols pull it off, gradually mastering how they give form to a certain human expression, edging closer and closer to how she herself can find a form to match what she wants to express. This protracted process is clearly visible within her drawings and paintings: drafts and mistakes are not entirely hidden from view, but stay very much in play, resulting in an instantly recognizable, wholly original style.

part two

|

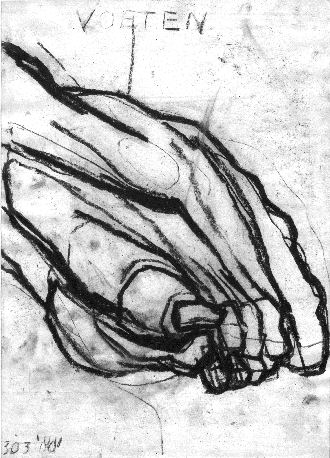

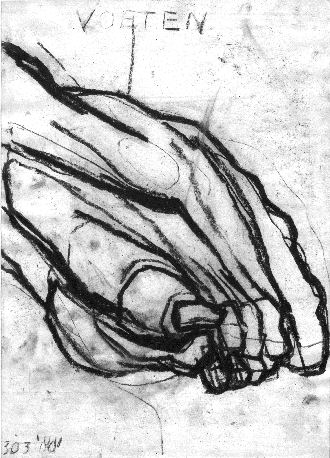

feet, after Grünewald, 1988

|